|

|

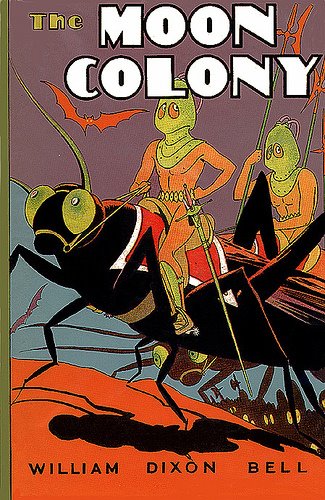

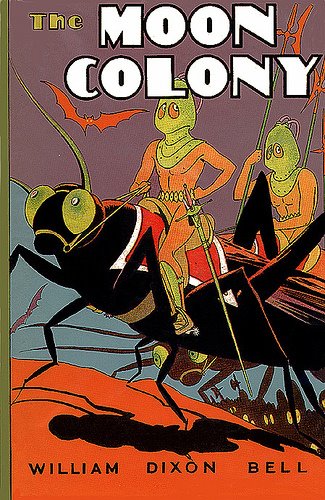

It's always great to make discoveries, and one of my recent discoveries is William Dixon Bell (1865 – 1951), whose career as an author is confined to some cowboy short stories published in the pulps during 1929 – 1931, and some very strange juvenile series novels aimed at teenagers. These include The Lost Aviators (1924), as well as two long-delayed sequels, The Secret of Tibet (1938) and The Sacred Simiter (1939), as well as The Searchers (1935) and what is probably his best known book, The Moon Colony (1937). His last boys' novel was Trailed by G-Men (1940).

To be straightforward about it, Bell is a chucklehead along the general lines of Ed Wood, Jr. and Arthur B. Reeve. He has not the vaguest notion of how people talk to one another, and even his narrative is sprinkled with wildly misused and misconceived language. The problem with Ed Wood seems to have been alcohol, while Reeve apparently suffered from circulatory problems that probably hampered the supply of sufficient oxygen to his brain. Bell's problem might have been simple senility, since his first juvenile was published when he was 60 and just retired from some career, and he was 75 when his last juvenile appeared; but he died about a decade thereafter at the ripe age of 86.

Bell is not much of a plotter, either. For example The Searchers and The Secret of Tibet have almost precisely the same plot. Bell is furthermore very little interested in his own creations, such as they are. In The Secret of Tibet our boy aviator heroes encounter a “lost civilization” somewhere in Central Asia, but apart from the fact that this lost race is “white,” we learn absolutely nothing about them. Their only function within the plot is to mine gold, which our heroes can ultimately fly away with. Similarly, in The Moon Colony, we learn that the earth's moon is inhabited by a bewildering variety of intelligent beings, but we learn absolutely nothing about them or their cultures and civilizations.

Bell's dialogue runs the narrow gamut from stilted to incomprehensible. When a Bell character wants to say “We're really getting into a rut, no doubt of that,” what he actually says is more like “We have rutted in place, and bank out that for fair.” Here's an authentic and in-no-way-extreme sample from The Secret of Tibet, [a novel which, by the way, has absolutely nothing to do with Tibet], with the speakers being an explorer named Curtis and one of our two boy-aviator heroes, Dave and Will:

“Shall we move on?” Dave asked as he seated himself at the controls.

“Straight ahead for a thousand miles,” Curtis instructed.

“My goodness, you must be a long ways from taw. I sure would have trouble thumping out the middle man that far away.”

Bell's The Searchers has my vote as the most nearly unreadable juvenile novel I have yet encountered, and I have encountered many. It doesn't become even remotely interesting until our set of boy heroes (they'll be high school juniors “next fall”), having set out on a large sailboat for the large island of Tiburon off the Mexican coast, instantly fall afoul of an implausibly large number of inexplicably organized Indians who live on Tiburon... who of course are also inexplicably somehow accumulating gold for our heroes to make off with at the novel's conclusion. Once the usual juvenile-novel sequence of captures, escapes and rescues begins, you can at least keep turning the pages in hopes of some action. What drives the plot is that an American Indian student and athlete, “Indian Joe” Wells, has a pathological hatred of one of our heroes, Bob Grinnell. There is not the slightest attempt to explain this hatred within the book; Joe and Bob barely know one another; they don't attend the same high school, are not rivals on the athletic field, etc. It's just necessary to the plot for one of the boys to be treacherous and evil and to hate the others, so he does, without rhyme or reason. It is even hinted that he is one of the Tiburon Siri Indians, although how he managed to wind up at “the famous Indian School in Arizona” is of course left a total mystery, never to be explained. In fact, in general, Bell's villains do very little talking and never justify themselves or their animosity in any terms whatsoever. Wells is evil because he's an Indian. The chief villain of The Secret of Tibet, “Prince” Scar Face Chang, is evil and out to get our heroes mainly because he's Chinese. Yellow Peril, indeed. A partial exception to the rule is Toplinsky, the Russian mad-scientist villain of The Moon Colony. He justifies himself (somewhat incoherently) at nearly every opportunity, but again one of the things that drives the plot, what there is of it, is Toplinsky's extreme animosity toward our hero, aviator and “secret agent” Epworth... and there is no real reason supplied for this animosity, it just is demanded to give some occasional action to the plot, which includes two violent, no-holds-barred fistic encounters between Toplinsky and Epworth. I've managed to find and read all Bell's juveniles except the first, and the only one where “foreigners” aren't depicted as inherently evil (with the exception of two beautiful and almost naked native girls, who of course instantly fall for our clean-cut young heroes) is The Sacred Simiter, where all the Arab leaders the two boy-aviators encounter are depicted as trying to work for the best interests of their people, even when this goal puts them at cross-purposes with one another.

Bell doesn't seem to have made a great success as an author of novels for teenage readers. His first juvenile novel, about identical(?) twin boy aviators, Will and Dave Hope, who fly non-stop across the Pacific in a vaguely described aircraft of their own design, the Bird of the Occident, whilst being sabotaged at every turn by evil rival aviator Hal Loftin, was published in 1924 by a very obscure publisher and never reprinted, but its sequel, although set in time immediately after the events of the first book, did not see print until 1938. Based on the number of copies I have seen in bookstores over the years, I'd guess that his only book with fairly good sales was the tepid science fiction adventure, The Moon Colony, and despite the sweep of its extraterrestrial goings-on, it provides very few rewards to the reader. However, to give it its due, it is nearly the only juvenile science fiction of the era that takes its cues from the rapidly-developing pulp-magazine science fiction of the day (1925 – 1935). Bell was anticipated only by Carl H. Claudy, who published four juvenile novels on what were quickly becoming stereotypical pulp-magazine science fiction themes in 1933 – 4. Claudy went Bell one better by also writing for the rapidly exploding late 1930s comic book industry.

Bell's last juvenile, which I recently found and read, is in many ways his most completely conventional. It has his trademark stiff dialogue, but the nearly incoherent plot, about two boy reporters, one of whom just happens to be the son of his newspaper's editor/publisher/owner, who has mysteriously disappeared just as a hidden criminal mastermind is poised to take over a large city, is by far the most generic of all his work for teenagers... in fact I have over the years read two other juveniles with nearly precisely the same overall plot. The book is full of absurdities, including an FBI agent who spends most of his time donning disguises and blundering into the headquarters of various criminals in hope of literally stumbling by chance onto some evidence. The two boys “assist” him by doing precisely the same. Apparently Bell was himself a newspaper man at one time, but the newspaper background is thin and quite unrealistic. Apart from a beautiful and somewhat frightening female villain, there is really nothing in the book of potential interest to readers either in 1940 or in the present day.

|

|