|

|

Even the briefest history of pulp magazines in the first half of the 20th century is far beyond the modest scope of this page. And even the briefest history of the genre of Old West Adventure pulp magazines is equally beyond our scope here. Suffice it to say that the apparent first pulp entirely devoted to cowboys, owlhoots and indians in the last half of the 19th century was Western Story, providing “Big, Clean Stories of Outdoor Life,” and first issued by Street and Smith in July of 1919. It was an idea whose time had come; silent films were strong on Western action, with stars like William S. Hart becoming household names... and as the sound era came in about a decade later, the Western was a reliable moneymaker in both A and B markets. The natural result was an explosion of Western pulps on the news stands... there were eventually more Western pulp titles being published than those for any other genre, and my impression is that the Western pulps were cumulatively the best sellers compared to all other pulp genres.

Now we come to the topic of the “[publishing] house name.” Editors would sit down and create a character, detail his origins and outline some of his adventures. The material would then be turned over to a willing author, who would write up publishable versions of the character's antics... and one of the series of stories or novels resulting would appear, usually, in every issue of the pulp from then on. The house name became uniquely associated with the particular character... The Shadow's exploits were recorded by the otherwise non-existent Maxwell Grant, while Doc Savage's investigations were written up by the famous but imaginary Kenneth Robeson. The reason for the house name was that, in principle, many different authors could contribute stories under this blanket, and writers who burned out under the load of a new novel every month could be readily replaced.

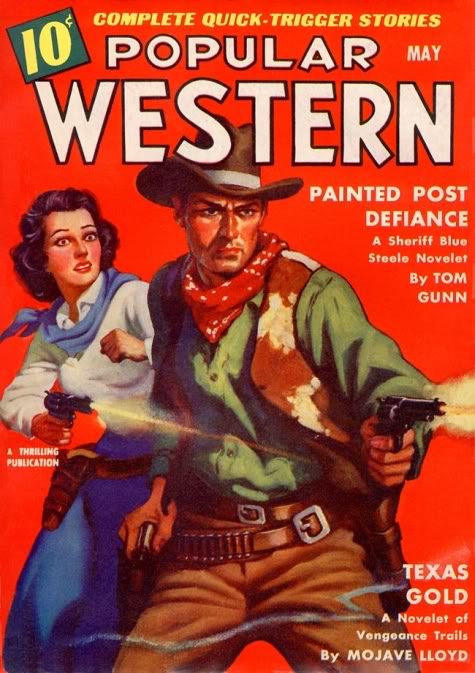

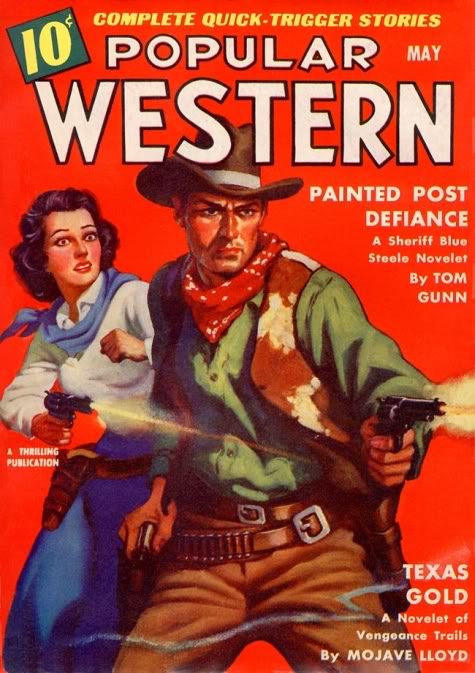

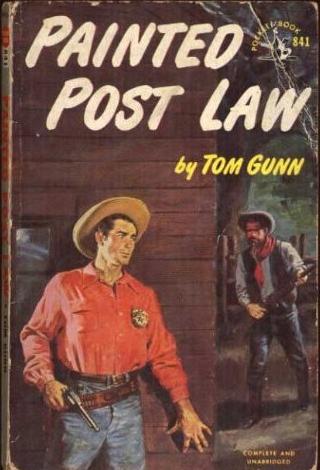

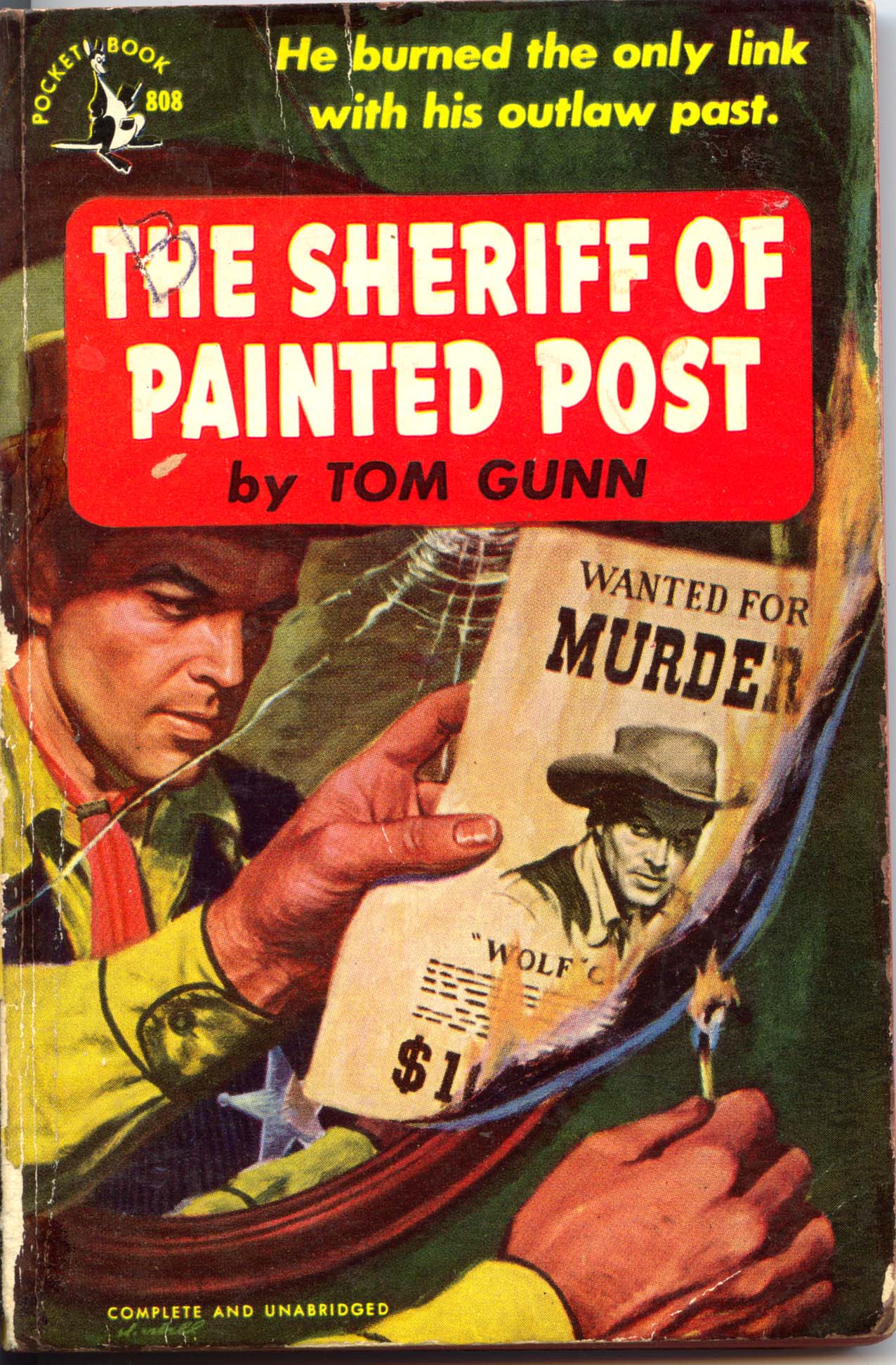

Recently I became aware of a house name used mainly in Popular Western magazine, namely the somewhat absurd “Tom Gunn.” The hero whose adventures “Gunn” generally chronicled was the equally absurdly named Blue Steele, sheriff of the tiny [imaginary] cowtown of Painted Post, Arizona. Eventually there were nearly 85 stories published under the Gunn name, mostly detailing (to use the word loosely) this hero's less-than-epic adventures, usually appearing in Popular Western, but also at times in Thrilling Western, Range Riders Western, Thrilling Ranch Stories, and West. A few of the Tom-Gunn-bylined tales were written, as far as I can tell, by veteran pulp author Frank Gruber. But the vast majority were pounded out by Sylvester [“Syl”] MacDowell. Now for the interesting part. These tales, as I read them today via 1950s paperback, come across as pretty rudimentary ranchers-versus-rustlers, sheriff-versus-outlaws junk... yet they must have been extremely popular with readers. The series continued from 1934, when the character was introduced in the serialized novel “Sheriff of Painted Post,” until the very end of the pulp era, 1953. And the first few novels in the series almost at once saw hardback publication, a very great rarity in the pulp era. The paperback explosion of 1950 brought these first few novels back into print yet again as widely-distributed Pocket Books, and Sylvester MacDowell was encouraged to put all the Blue Steele novels into renewed copyright in 1962, which is how I was able to identify him as author. MacDowell himself had a long life (1892 – 1980), and Blue Steele seems to have earned him a fairly steady income... at least from 1934 to 1953.

MacDowell didn't devote much time to these tales. There is generally no plot, just a series of incidents, each of which stands pretty much alone in the context of what might happen before or later in the tale. Everything is simplified to the point of near-absurdity. Thus, Painted Post has one restaurant, run by the amiable Chow Now... does it not occur to MacDowell that to run a restaurant you need a cook, waiter, etc.? There's just Chow Now. Similarly there's only one large, nearby ranch, and the owner seems to be the only judge accessible from the town. There's apparently only one saloon, and the owner is also the bartender. There's only one of everything, stable, hotel, store, bank, etc., and only one named character associated with each of those things. Thus, Steele the sheriff has only one deputy, a stereotypical red-haired bumbling character named Shorty Watts. And often Watts is left behind as Steele goes out to face a dozen or more rapscallions alone... explaining to Shorty that otherwise those bad men will have no respect for the sheriff's office! Thus, if you're expecting the epic mythmaking of Max Brand, or the realistic characterizations of Luke Short, you're barking up the wrong tree. What Gunn/MacDowell provides is a very simple, straight-ahead linear tale that sets up violent gunplay every few pages. There's none of the rapsodical description of the landscape that many writers provide. All characters are constructed of the thinnest cardboard, and psychological development is never even hinted at. The reader gets quick gratification for his dime. As movie reviewer Joe Bobb Briggs used to say, “no plot ever gets in the way of the story.”

|

|

That extreme simplification is of course deliberate. It was probably decreed by the editors of Popular Western in their original design of the character and his town. There were two reasons for the stripping-down. First, it made it simple for various writers to take over the series if and when that became necessary. A single sheet of 8 x 10 paper would contain the entire background that the new author needed to know concerning characters and locales. Second, the level of reader aimed at was an exceedingly low level. The “house” series was generally an entry-level series, intended to be accessible, exciting and friendly to the kid who had picked up this pulp issue on impulse, and tossed down his dime, but had never read a western story before. There was always a Tom Gunn tale listed on the cover— the kid could be sure of finding just the kind of story he liked, about the same characters, the next time he spent his dime on Popular Western. Those were the days, my friend. One final note: how did Frank Gruber wind up publishing some stories under the Tom Gunn pseudonym? The answer is that one-man-fiction-factories like Gruber often had two stories accepted and scheduled for publication in the same issue. It was customary, in those cases, to use a pen-name for the lesser of the two tales. If there were no MacDowell-penned Blue Steele tale in the hopper, then some story by another author would be assigned to the Tom Gunn label, so that the cover of that issue could as usual advertise the latest work by good old Tom.

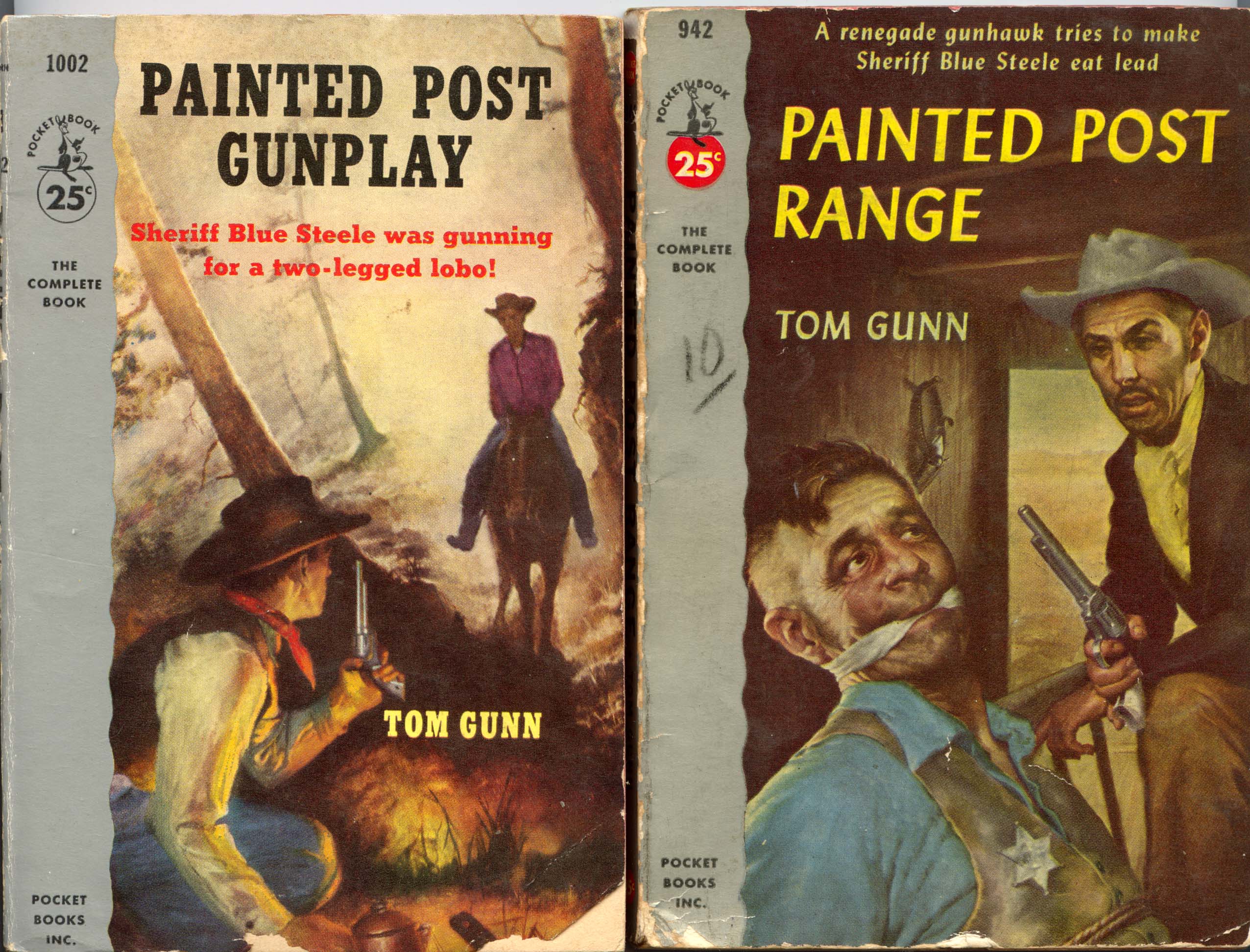

I have now read all four available paperbacks in the set, and by far the best

is Painted Post Gunplay

[1937]. This one has Steele and Shorty stuck in peril in Mexico whilst

Painted Post itself is converted into a virtual ghost-town by one of

the villains, and a continuing character in

the series is actually killed off about midway in the story. All of

these “novels” are actually three to four

short stories joined together. The action begins usually with two

villains; one is killed off about one-third of

the way through and a new villain appears to join up with the surviving

owlhoot. Then one of these is killed off

about 2/3-rds of the way through, and a final duo of bad guys forms up

to be gunned down at the finish. No outlaw

survives for more than about 2/3 of the text of each novel.

By the time of Painted Post Roundup (1939), things have changed quite a bit. There is much less violence, and the sheriff tends almost always to “crease” the villains instead of blowing their hearts out through their backs. There is much more description of the Arizona countryside through which the characters are incessantly riding. The pace is much slower, and consequently the novels are longer... Roundup is so wordy that the Hillman digest version actually had to be abridged to fit into the format. While the regular town characters are not multiplied in number, a much larger than usual cast participates in the adventure and the occasional action. The novel maintains a sort of unity, and does not obviously divide into individual short stories. I would guess that this steady trend continues, so that by the early 1950s there was not much difference between the Painted Post novels and the usual pulp western novels of the day.