Psychic

Detectives!

|

The

Psychic Detectives! |

|

· CLAIM: Psychics have the power to “see” things in the past, present, and future that ordinary people cannot, and as a consequence of this, the police regularly consult them for help in solving crimes— particularly crimes involving missing persons or homicides— when their own investigations stall.

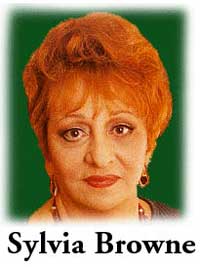

· FACT: The overwhelming majority of police officials are highly skeptical of alleged psychics, and are very rarely if ever responsible for inviting them to aid in their investigations. Often, the police treat psychics just as they treat other “kooks” who gravitate to major crimes— politely, but disinterestedly. The Los Angeles police department once conducted an experiment to test the value of information obtained from psychics, and concluded that it was of absolutely no value (see references below, including Journal of Police Science and Administration, March 1979). Nothing has changed since then. In two highly publicized cases, a couple of decades ago, numerous psychics made pronouncements about a series of murders of black teenagers in Atlanta, Georgia, and the kidnapping of General Dozier, yet absolutely nothing of value resulted. Indeed, most of the assertions made proved to be so grossly in error as to be laughable. (For example, none of the psychics believed Dozier to be alive, yet he was released unharmed.) These are not isolated cases; they are completely typical of the “successes” of so-called psychic detectives. Such grotesque and continual failures have had no impact on public credulity, because a different impression about the achievements of the self-proclaimed “great psychics” is typically gained from the news media, and that is invariably due to their allowing the psychic to keep his own score. That is, the psychic will make dozens of (often vague) statements and then after the case is settled will select the items that, by chance, had some truth to them and will proclaim them to have been accurate predictions. In one noteworthy instance, a famous psychic proclaimed to the press that she had given the name of the Atlanta serial killer to the police, when in fact she had given the police 42 names! And many of those were the same names that the police had shown her because they were already suspects; the person eventually charged was on the original police list shown to the psychic. A recent case is completely typical: an 11-year-old boy, Shawn Hornbeck, mysteriously vanished while out riding his bicycle on October 2, 2002. Ace psychic Sylvia Brown told the shocked parents on live TV on February 26, 2003 that Shawn was dead, and provided vague details on where his body might be found, and a more specific description of his killer. In January of 2007, while tracking down another kidnapped child, police found Shawn alive and well, having been held captive for more than four years. His kidnapper in not the slightest degree matched the description given by Browne.

· CLAIM: Psychic detectives have been responsible for solving numerous cases that had the local police totally baffled.

· FACT: There is not a single documented instance of a crime being solved on the basis of information gained from a psychic, and there are numerous instances of police officials denying a psychic’s claim that numerous pieces of information were unknown until the psychic revealed them. (Note that there is a difference in procedure here and that it works to the psychic’s advantage: the police tend to keep secret certain important details of a crime, whereas the psychic seeks media attention and is likely to make public anything he might uncover that has not already been revealed.) Often the reports of crimes that are claimed to have been solved by a psychic come from the psychic personally or from an observer or reporter who did not independently investigate the facts behind the claims. As a consequence, the public receives an uncritical version presented as fact, and when police or experts then try to set the record straight, the newspapers and TV news either ignore them or insert watered-down retractions in obscure locations. One way the process works is that the psychic will find out as much as possible about the circumstances, terrain, etc., from one policeman, family member, or other source— either before or soon after arriving on the scene— and the psychic will then “re-package” that information to another policeman or family member, or to the media. This second party is often (understandably) amazed at how much the psychic is able to relate about the circumstances of the event, but of course the psychic is actually doing nothing beyond what any devious person could accomplish without the aid of alleged “visions” of the past and future (examples of this procedure are discussed by P. H. Hoebens and others in the references below). Some of the more famous psychic detectives have carried this procedure to an extreme; they come to the crime scene prior to their publicly announced arrival and, using disguises and/or subterfuge try to gather inside information for later use in their allegedly psychic reports. Psychic detective Peter Hurkos, for example, was arrested and fined for impersonating a law enforcement official while trying to gather information about a crime he had not been requested to assist with.

|

|

|

· CLAIM: Since the psychic sleuths’ powers are a gift with which to do good, no fee is charged; in fact, to charge might jeopardize the powers.

· FACT: When not sleuthing, and most of the time they are not sleuthing, almost all psychic detectives earn a living by doing other allegedly psychic things, such as giving readings at private sessions, and these other activities are definitely not done gratis. Thus, the psychic sleuthing accomplishes several things: (1) it establishes the psychic in the public eye as someone who possesses extraordinary powers, (2) it imbues him with an air of respectability, and (3) it gives him free publicity that would be very expensive if purchased outright. (As an aside, one wonders why someone who does have the power to see the future, and who truly was concerned enough about the ethics of such a gift not to charge for its use, does not use that power to benefit mankind— as for example by revealing the impending occurrence of natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, tornadoes, etc. Surely such use would not jeopardize the power.) It should be noted that even when psychic detectives do not charge money for their questionable services, it is not true to say that no cost is involved. Surely there is an additional emotional burden on the already distraught relatives of the missing or murdered person. This is illustrated by the circumstance that psychics almost always announce that a missing person is dead, and provide vague, unverifiable visions of where the body is hidden. Psychic detectives shamelessly prey upon innocent victims in times of great emotional strain, and because of this fact alone they deserve scorn, not yet more free publicity.

· CLAIM: By touching or holding an object owned by the missing or dead person, the psychic can get an impression or vision of the circumstances of the crime.

· FACT: There can be no denying that much can be learned about an absent person by examining objects owned by him or her. If one of the objects were a shoe, for example, the size, style, age, condition, and pattern of wear on sole and heel could all be helpful in sketching out a rough picture of the person. In general, at least, men who wear boots, wingtips, loafers, and sandals tend to be different in predictable ways, and unusual wear patterns can often be associated with particular walks. Similarly, the type, style, condition, and expense of a woman’s jewelry (a favorite object for psychic crime solvers) can be very informative about her. This is to say, logic and training can allow someone to make a number of good guesses about the owner of various objects— a point made in Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales repeatedly— without the necessity of any alleged psychic powers. However, in practice that kind of reasoning is too difficult for most psychic detectives. Instead, they tend to pocket small but recognizable personal effects of the missing person secretly, and then “find them” whilst investigating what they identify psychically as the true crime scene— thus proving the police are stupid (they didn't find the item!) and the psychic is a wonderworker (he did!).

· CLAIM: All psychics are careful to assert at the outset that they are not always exactly right, and therefore no one should expect each of the impending announcements to prove accurate. The explanations for this problem are numerous. They often include (1) comments about how the psychic information sometimes comes as symbols and that the psychic sometimes errs when interpreting the symbols; (2) mention of the fact that in their “visions” time is confused and things yet to occur get misinterpreted as things that have already occurred; and, (3) comments about how the circumstances surrounding this event are particularly difficult for some reason that may include the time elapsed since the event, the presence of too many skeptics, etc.

· FACT: One obvious function of these immediate disclaimers is to protect the psychic in case, by chance, absolutely nothing he or she says can later be interpreted as being even partially correct. Another function is to get the believers and the uncertain persons in the TV audience to begin (unconsciously perhaps) to pull for the poor, sincere psychic who is going to try to overcome overwhelming difficulties in order to help the dumb, short-sighted police. A Dallas, Texas, psychic claims that 20% of the time he is completely right in his predictions. Beyond the fact that this statistic has never been verified— that is, he is being allowed to grade his own papers— there are the problems of what counts as correct and what his true error rate is. Regarding the first problem, psychic detectives often use vague terms like “I see nearby trees or shrubs or tall grass,” which cannot possibly be wrong given local terrain, or “look to the left of the barn,” which after the fact can be scored as correct by simply assuming the appropriate location for the viewer. If clues like these count toward the 20% number, it is difficult to understand why it is not a much higher value. Second, in order to accurately evaluate a psychic’s performance it is necessary to know the number of both his correct and his incorrect assertions. A medical test that accurately detected 99% of the people having a disease (the “hits”) would be of little practical value if it also falsely identified 95% of the disease-free people as having that disease (the “false alarms”). Were any psychic detective ever to allow a careful, scientific study of his powers, both hits and false alarms would have to be measured.

· CLAIM: Whether right or wrong, information provided by self-proclaimed psychics can be very useful in police work.

· FACT: Nothing could be further from the truth. Any crime which gathers much newspaper publicity results in many crank telephone calls pouring in to the police. Such calls actually hamper the investigations, since someone must check them out, and this takes time away from other necessary police work. A self-proclaimed psychic’s contributions are equally unwelcome. Consider the elementary fact that police are looking for hard, physical evidence linking suspects with crimes, evidence that will stand up in court. Typically, a “psychic detective” will say, “I gave the name of the killer to the police,” and leave town, his publicity earned. But police generally have a pretty good idea who committed any given crime— they already know his or her name, that’s not the problem! What they need is evidence! In other words, even if psychic detectives did exist and really could provide correct information by supernatural means, the information would be worthless to the police because it would not be backed by any actual evidence that could be taken into court. And self-proclaimed psychics in fact and in the real world provide floods of nonsense, wild guesses, and unsubstantiated opinions— not valid information; they are thus many steps removed from being useful at any stage of police work.

P. Hurkos |

G. Croiset, Sr. |

Click on this photo! |

A. Owen |

FOR FURTHER READING—

Skeptic's Dictionary entry on psychic detectives. Results of a survey of police use of psychics can be found here. Psychic Detectives: Media versus Reality. An investigation of a typical US psychic detective.

Acknowledgments— Dr. Dennis McFadden, Professor of Psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, is the author of this fact sheet. The International Cultic Studies Association (formerly American Family Foundation), a professional research and educational organization concerned about the harmful effects of cultic and related involvements, prints and helps distribute these fact sheets. Because such fact sheets seek to stimulate critical thinking, rather than advance a particular point of view, opinions expressed are those of the authors.